Update: since I wrote this page I found and bought a boat for this adventure. Find more about Changabang here.

Most sailors who spend a long time at sea seem to develop an intimate relationship with their boat; it is after all the only thing that keeps them away from death. Choosing a sailboat is, therefore, a very personal matter. It must feel right to the skipper. That’s not all though … It must be fit for the purpose too. Let’s see what a sailboat to circumnavigate Earth looks like.

If you’ve checked the course you know a few things about the dangers that this sailboat may face and the conditions in which it must excel. Many things have been written about what a proper sailboat should be for a circumnavigation. See this for a great article. And there are some serious offshore machines available on the market. However, limited funds will force some hard choices.

Strong

Ok, so we’ve decided that we don’t want the boat to sink, lose its mast or generally break. Most of these risks can be mitigated with solid construction. Boat builders have used the following material for construction:

Most sailboats were built with a time horizon that was significantly shorter than their current age. Finding a used sailboat to circumnavigate is a little like looking for a used car from the 80s to drive it from the tip of South Africa, through Europe, Russia, America and all the way down to Cape Horn. It doesn’t sound like a great idea; the body is probably rusted to the core! We’re lucky though as there are very strong sailboats available on the market because some boat builders took their work seriously when building boats designed for offshore sailing. And they can be repaired.

Resilient

In the event of a hard grounding at speed or hitting an object, we don’t want to lose the keel or the rudder, which, being so deep in the water,

Oversized

Besides the keel and the rudder under the water, above the water, the mast appears to be a very fragile piece of the boat. In fact, it is designed to take very heavy loads by transferring forces to the hull through a series of cables and attachment points. Making sure that this setup is oversized increases the chances that the mast will stay up

To save weight (go faster) and limit cost, most sailboats are designed to take loads that one would encounter through day sailing, not sailing through a hurricane and repeated beatings. We’re most likely going to have to beef up this part of our boat.

Limiting our choices

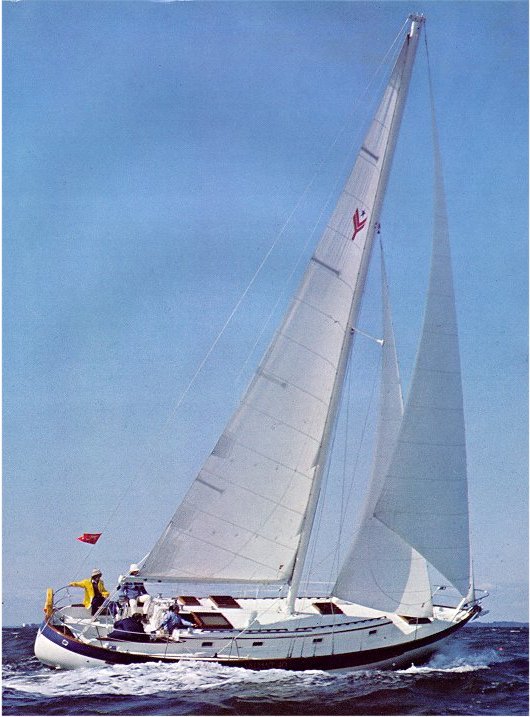

For a couple of reasons, we have decided to limit the boat’s length to 40 feet. Full keel 36 feet sailboats were considered the right size for offshore work. As an example see the Golden Globe Race boat requirements. Then 50 feet it was, and now, most offshore sailing races are aboard 60-70 feet sailboats. Even cruisers have seen their boat increase in size by 10-15 feet over the past two decades. Maintenance and preparation costs grow almost exponentially with boat length. Keeping the boat small is one way to control cost. Since sailboats are often categorized according to their length (<40 ft; 40-60 ft; >60 ft), we decided to pick something in the “small” category.

A few bonus points!

In addition to the litany of safety requirements (as an example see the safety requirements for the Singlehanded Transpacific Yacht Race on

- Keep moving in light air (<5 knots of wind speed): there will be difficult passages where keeping the boat moving in light air and strong tidal currents will be critical to the safety of the boat;

- Sail to windward fairly efficiently in a gale or more (without crew on the rail), as there will be several passages where this situation is very likely to occur;

- Generally, be a fast boat (i.e. a PHRF rating around 50);

- Sail to its potential without requiring complex sail adjustments, such that the boat can be kept sailing fast with a single soul aboard.

An excellent choice would be a boat of the Open 40 or Class 40 type. But they’re over our budget. So we’re looking at other choices. If you know of good candidates please let us know.